How a WebRTC SFU works - Developing a WebRTC SFU Part 1

Opening

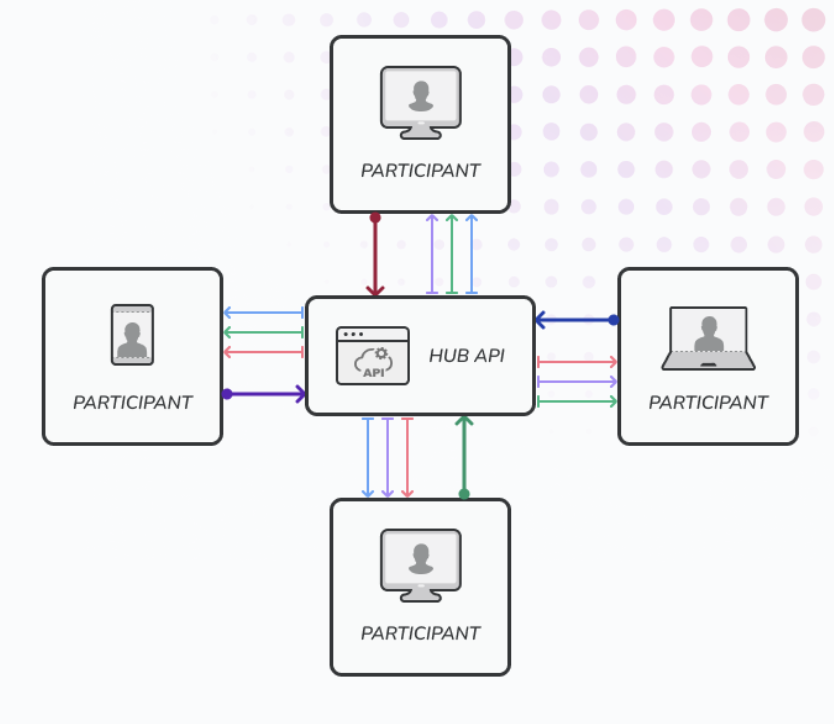

An SFU(Selective Forwarding Unit) is a WebRTC architecture that will route the media stream from one peer to another peer in the same group. The SFU is design to make the group video conference scaleable with low latency. Other architechture options are MCU(Multipoint Control Unit) and Mesh. MCU is hard to scale because it will need a lot of CPU power to composite the media stream. Mesh is not scalable because it will need a lot of bandwidth to send the media stream to all peers in the room. You can learn more about the WebRTC architecture in this article.

When we design our SFU, we focus on making the SFU portable and can be extend later. You can read about how we design our SFU in this article. This post we focus on what the we learn we we developing the SFU. This will be a series of blog posts because it will be hard to cover everything in single post. In this series, we will cover the following topics:

- How the SFU works

- Challenges in developing an SFU

- Signal negotiation and renegotiation

- Codec negotiation

- Improving join and leave experiences

- Deployment

Let’s start with the first topic, about how the SFU works.

How the SFU works

A basic SFU is put together all peers in a virtual room, then allow them to send their media streams to the group, and the group will broadcast it to all peers. The peers can selectively choose which media stream they like to receive, depend on how we design the SFU. The basic SFU usually came with the following components:

1. Virtual room or group

This is a group of peers where the peer will join to interact with other peers within the group. It can be just a simple map or array of WebRTC clients that connected to the SFU if the SFU is just run in a single server. But if you run the SFU in a cluster, you will need to find a way how to unify the same group from multiple instance of SFU. You will need to think about this when you’re planning to have a distributed SFU to reduce the latency by running the SFU in multiple regions. How a user who join in a region can see the other peers who join in other region? We will cover this in the deployment section.

2. Signaling server

This is a server where the browser or the WebRTC client will negotiate the connection. Usually this is will be a socket or HTTP server. The signaling server must be bidirectional, because the WebRTC client will need to send and receive SDP and ice candidates to or from the SFU.

There is a draft standard of signaling protocol using HTTP called WHIP (WebRTC HTTP Ingestion Protocol) and WHEP(WebRTC HTTP Egress Protocol). Some of the SFU and live streaming client already support this protocol. The only thing you need to note here, the ingestion and egress will use two connection.

When you’re planning to have a multiple region SFU, then the signaling server will responsible to connect the peers to the nearest SFU server. The easiest way to do this is by using a load balancer that will redirect the connection to the nearest signaling server, then the signaling server will use the SFU server in the same region. We will cover this in the deployment section.

3. Media stream forwarder

This is the main component of SFU which responsible to receive the media stream from the peers and forward it to the other peers in the group. This component usually will be a WebRTC client that run on the server. This is the core component of SFU and should be your focus when you’re trying to design a efficient and high performance SFU server.

There some optimization can be done here like using a single port for multiple WebRTC clients for easier deployment, or pause the track relay if no one consume it to reduce the CPU usage. There will be a lot of small details here to optimize the performance of the SFU. We will cover this in the next posts.

The Flow

To understand how those components above works, let see what happens if you are join a Zoom Meeting or Google Meet. This is how it works behind the scene.

- The invitation will always come with a URL that contain a unique room id. The room id is used to identify the virtual room to join. A meeting host is responsible to create the room and get the room id to invite others.

- When you click the URL, your browser will open and connect to the signaling server. The signaling server basically help you to negotiate the connection between you and the SFU server by exchanging SDP and ice candidates. The SFU here basically the same WebRTC client like your browser, but it’s run on the server. For each client, there will be a single WebRTC client will created on the SFU to establish the peer to peer connection between your browser and the SFU.

- When the negotiation happen, your browser will send an offer SDP to let the WebRTC client on the SFU know that you’re like to connect. This offer SDP includes the detail of media stream that you like to send, capabilities of media stream that you can receive, and network information like your IP addresses, and network port to use. Once received, the WebRTC client on the SFU will respond with the same details in the answer SDP. Once you both agree on the details, the connection will be established.

- When the connection established, your browser will start sending the media stream to the SFU. Your pair WebRTC client on the SFU will receive the media stream and forward it to the each WebRTC client in the room who also a pair for each peer client in the group.

Closing

Those are the basic flow of how an SFU works. Developing a simple SFU can be done in a week, but to make it production ready, it will take a lot of time. We will cover more about the challenges in developing an SFU for production in the next posts. Stay tuned!